Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Languages

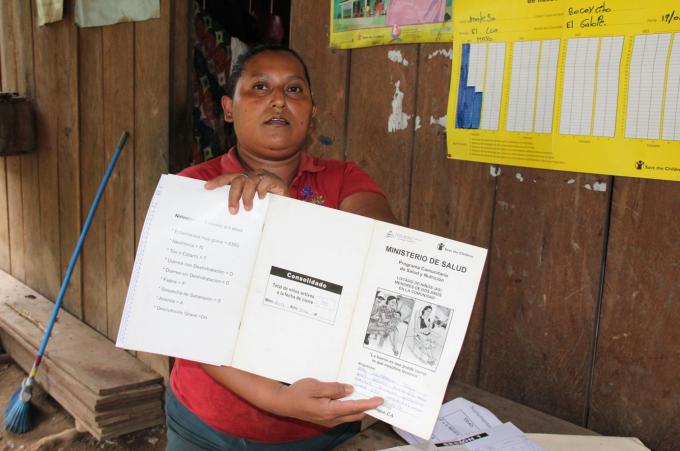

“A community health worker who is passionate about her work”

“A community health worker who is passionate about her work”

|

Name of the child (person) |

Juana Lidia Hernández Orozco |

|

Town or Department |

The community of El Galope in Jinotega, Nicaragua |

|

Age |

37 years old |

|

Sex |

Female |

|

Current family context, where they live, their daily lives, the school where they go, difficulties faced as a family. |

“One of the things that most satisfies me as a community health worker is having saved the lives of two girls with pneumonia that I referred to the health center and that the doctors said would have died if hadn’t identified the danger signs.” This is the inspiring story that 37-year-old community health worker Juana Lidia Hernández tells us right away. Juana Lidia is from the community of El Galope, located in the very south of the department of Jinotega and surrounded by high and densely forested mountains, some 250 kilometers north of Managua.

It is a quite difficult to access this community by vehicle. The most frequent means of transport is by horseback and only one collective transport bus enters every day, making it hard to transport a sick child to the nearest health post, which is 20 kilometers away, or a two-hour walk.

Juana Lidia, known as the “little doctor” in her community is the reference point for many mothers seeking medical advice or care for their children. She lives with her husband, 40-year-old Ricardo López, and her 13-year-old son Mynor López Hernández.

“Mothers from this community have come to knock on my door in the middle of the night many times to provide care for the children they bring who are sick with pneumonia, diarrhea, headaches…” Juan Lidia tells us. “I let them know they don’t have to worry about coming and looking for me whatever time it is.”

Her work as a community health worker (known as a brigadista de salud in Nicaragua) began with the birth of her son, Maynor. From that moment she started to be aware of the attention and care required for a newborn baby and the treatment that needs to be provided during illnesses.

When Maynor was just six months old, she was invited to a community assembly to replace a leader who was going to leave the post of community health worker for personal reasons. Juana Lidia was surprised when the assembled community proposed her to fill the vacant position.

“Thirteen years ago I was chosen in this community to take on the post of community health worker that the Ministry of Health (MINSA) required as a liaison to record the statistics and provide community health services,” Juana Lidia explains to us. “I started by weighing, measuring and providing health care to my son and since then I’ve found the community work to be satisfying, although it’s pretty hard and voluntary.”

One of biggest challenges Juana Lidia faces every day is the lack of support from the community. She feels they often leave her alone and there is no other community health worker to replace her if she is out of the community at MINSA training sessions or attending to personal matters.

“The community doesn’t want me to quit because they think I’m doing a good job and because I have a lot of knowledge that other people don’t have,” says Juana. “But I’ll need a replacement in the medium term.”

As a community health volunteer, Juana Lidia is responsible for implementing three high-impact community strategies in her locality. The first is the Community Health and Nutrition Program (Procosan), whose objective is to monitor children’s growth with respect to weight and height. As well as monitoring the weight and growth of children under the age of five, in the monthly sessions she also gives the mothers advice on breastfeeding and the type of food they should give their children.

The second strategy is Community Case Management (CCM), through which Juana Lidia treats illnesses like diarrhea, fevers and respiratory illnesses. If the case merits closer attention, she is authorized by MINSA to refer patients to the nearest health center. Those child patients have a purple-colored scarf tied around their head or arm. “When the doctors see this sign on a sick child the patient receives attention right away,” she explains, proud of the work she does. “That means the mother doesn’t have to wait in long queues at the health center for her son or daughter to receive medical attention, as that child is a delicate state.”

CCM’s main objective is to classify illnesses, treat them and provide suitable counseling in the community on the use of medicines and the food that should be given to a sick child. Juana Lidia has a small first aid kit provided by MINSA to treat these illnesses, which belongs to the community. It contains amoxicillin for use against infections caused by bacteria, furazolidone for diarrhea or dysentry with blood, iron, oral rehydration salts, zinc tablets and acetaminophen for head and body aches.

Juana Lidia starts to give us examples of cases and the different steps to take to care for a child. “I’m the one who has the medicines: amoxicillin, oral rehydration salts, zinc tablets, furazolidone, acetaminophen in tablets and in drops...” she says. “The mothers show good acceptance of what I tell them and I have to explain to them carefully how they have to give the medicine and ask them if they understand how they have to do it.” Although she is a shy woman, it is obvious she is proud about her work.

In addition to supporting her community through the Procosan and CCM community health strategies, Juana Lidia advises mothers on guaranteeing safe maternity and avoiding risks during childbirth. This strategy is known as Plan Parto (the government’s strategy for providing pre-natal care to pregnant women in rural communities) and consists of avoiding maternal deaths through the counseling she gives to get mothers to attend their monthly check-ups in the institutional health centers and have their children monitored by qualified medical personnel. Following child birth, she also monitors the newborn child’s health status.

“It is a chain that happens from pregnancy. The child is monitored from the first month in the mother’s womb,” Juana Lidia explains.

An ideal day Every day Juana Lidia gets up at 4:30 in the morning to get her son ready for school and prepare the food for her husband Ricardo, who leaves at 5:30 to work as an agricultural laborer in the nearby coffee farms.

“After my husband leaves I stay awake doing the household chores and getting my son ready as he also sets off early to go to school,” she tells us.

An ideal day for her is one in which everything goes well during a weighing session: “I feel really happy when I see the mothers come to monitor their kids’ weight and height, being able to guide them and congratulate them on the things they’re doing well with respect to feeding and looking after their children, letting them know how important it is to prevent rather than treat. That’s an ideal day for me.”

However, this work implies a lot of time and effort for Juana Lidia, who divides her time between being a housewife, attending to the health problems of the community’s children and doing extra jobs like washing and ironing clothes for neighboring households. In addition, she and her husband take advantage of the coffee harvest in the last three months of the year to earn income and help maintain their household.

“Although I like being a community health worker, sometimes it complicates my life too much because my husband works in the fields and I also have to work,” Juana says. “Sometimes I even neglect my family and my house because I’m going to training sessions and I have to balance my time between being a community health worker and earning a living for the house.” |

|

Description of the house and the family environment, their attitude, their look, their expression when you talk to them, their interests, ambitions |

Juana Lidia and her family live in a modest house built out of wooden planks and with an earth floor. The house has a single bedroom where she sleeps with her husband and their son, Maynor. It also has a small living room and a small clay stove where they prepare the food.

El Galope is a small community with just 120 houses. The inhabitants all know each other and the place is very healthy. The community’s main economic activity is coffee production and cultivation, followed by cattle ranching.

This family’s vision is to grow and produce its own foods in the future. They have already been selected for the food security project to start working on the small-scale production of basic grains. “Save the Children has benefited us with seeds and a metal silo to implement the production of basic grains and have food throughout the year,” Juana Lidia tells us. |

|

Their views! - Please write down their exact words related to all aspects of their history, what happened, why and when, how they feel today, as it affected the project. |

“I’ve saved the lives of two girls with pneumonia because I identified the danger signs we’re taught by the MINSA health personnel in the training sessions.”

“There’s nothing more gratifying that seeing a healthy child that has the right height and weight, or seeing a pregnant woman that has all the necessary care, whose child is developing well and that will give birth to a healthy son or daughter. I’ve been through all of these experiences as a community health worker and that makes me very proud.”

“My house functions like a medical post, where care is provided to the children, counseling is given using the illustrated laminated sheets that Save the Children gives us, and medicines are supplied.”

“One of my biggest dreams is to expand my house as during the monthly weighing sessions we don’t have enough space to sit the mothers down and I want to attend to them well.” |

|

Any other quote of the girl or boy. |

“I like being a community health worker. You feel more integrated. The community has changed a lot since we’ve had CCM and we’ve very grateful to the program for the benefits it’s provided.” |

|

Comments of the family; promoters of the program, community members. |

For Carlos Jarquín, a technician working with the Save the Children health program, “Juana Lidia is one of the most experienced community health workers we have in this area. The work she does is even recognized by the health post personnel and the community is happy with her efforts.” |

|

Background information on the Save the Children project in which they have been involved. |

In 2007, Save the Children innovated and tested the Community Case Management (CCM) approach with the specific aim of tackling the high under-five mortality rates in areas that health services were not reaching. To date, Save the Children’s CCM approach has reached 4,000 children in 120 communities, demonstrating its effectiveness in decreasing infant mortality by 50% through a sustained, high-quality, community-based service that provides prevention, treatment and, where necessary, referral. Convinced by the evidence of CCM’s effectiveness, the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health has been partnering with Save the Children in the implementation of the approach and in planning for a national scale up to all of the country’s remote communities. When implemented, this scale-up plan will ensure greater equity in survival rates for all Nicaraguan children.

In 2013, recognizing the established evidence of CCM’s effectiveness and the real potential for scaling it up to the national level through a partnership with the Ministry of Health, Save the Children approved the CCM as a signature program. The scale-up plan was based on Save the Children’s capacity to expand the program to 761 communities in partnership with MINSA.

CCM saves lives through increased use of preventive and especially curative interventions delivered by trained community health volunteers in remote, rural areas of Nicaragua, which are often at least 2 hours from the nearest health facility. The program ensures the accessibility of preventive and curative lifesaving health services for young children that are delivered with high quality and according to protocol, are appropriately and promptly sought by families, and are supported by appropriate community structures and national policies.

CCM is particularly effective in reaching the most disadvantaged children because it provides cost-efficient, accessible lifesaving solutions for communities and children who are otherwise excluded from or deprived of health services due to distance, poverty, knowledge and behavior. It leverages and strengthens human capacities within communities, extends government health services and supply chains through efficient networks, provides consistent quality assurance monitoring systems and partners with national systems to continuously monitor and track impact.

In partnership with the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, Save the Children’s CCM is implementing the following strategies:

(1) training selected community members as frontline community health workers to assess, classify and treat children with signs of infection; (2) strengthening the Ministry of Health at the local level to support, supply and supervise these community health workers; and (3) training families to recognize signs of illness and promptly seek appropriate care for sick children.

Community health workers are often the first, and sometimes the only, source of health care in these villages. They provide vaccines to prevent childhood illnesses; advice and information on better delivery, newborn care practices and breastfeeding; and curative interventions, such as antibiotics for pneumonia and dysentery, drugs to treat malaria, and oral rehydration salts and zinc for diarrhea. |

|

|

|